Exhibition text Kunsthal Rotterdam

Isometrix at Kunsthal Rotterdam 2021

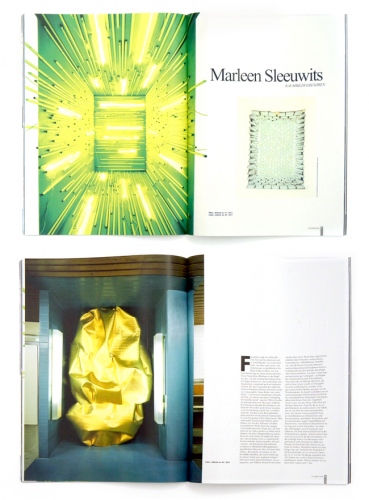

Am I looking at a photographic print, or is this part of the building? The installations of Marleen Sleeuwits (1980) blur the dividing lines between fiction and reality. Aided by bright neon lights, foil, photographic prints, and mirrors, she plays with perspective, reflection, and scale in architectural spaces. Examples of this are windows that continue beyond the ceiling, or the repetition of architectural details. It is her intention to temporarily alienate the visitors from their sense of time and location. Sleeuwits will be transforming the display window along the ramp into a spatial optical illusion for Kunsthal Light #24. She is inspired by the Kunsthal architecture that in her view contains elements of beauty and disorientation.KUNSTHAL LIGHT

‘Kunsthal Light’ is the Kunsthal’s talent development programme. Since 2011, this exhibition programme has been especially focusing on young artist who are capable of making 'a grand gesture' in an original and artistic way. Three times a year, the Kunsthal places HALL 6 (the over 25-meter-long display window along the ramp) at the disposal of an artist who is given free rein to make a site-specific work. In 2020, Kunsthal Light is also made possible by the Mondriaan Fund.Nederlandse versie:

Kijk ik naar een fotoprint of is dit onderdeel van het gebouw? In de installaties van Marleen Sleeuwits (1980) is de grens tussen fictie en werkelijkheid vaag. Met helder neonlicht, folie, fotoprints en spiegels speelt zij in ruimtes met perspectief, reflectie en schaal. Vensters lopen door in het plafond of architectonische details dubbelen bijvoorbeeld. Ze heeft als doel bezoekers voor even te vervreemden van tijd en plaats.

Voor Kunsthal Light #24 transformeert Sleeuwits de etalage langs de hellingbaan in een ruimtelijke optische illusie. Zij laat zich inspireren door de architectuur van de Kunsthal, waar voor haar elementen van schoonheid en desoriëntatie in zitten. Terwijl de Kunsthal voor publiek gesloten is, start Sleeuwits op maandag 18 januari met de opbouw van haar installatie ‘Isomatrix’. Vanaf de hellingbaan buiten is te zien hoe haar project vordert. Zodra de Kunsthal weer open kan, is Kunsthal Light #24 te bezoeken.Voor de realisatie van haar site-specific werk ‘Isomatrix’ neemt Sleeuwits interieur en exterieur van de Kunsthal eerst met haar camera in zich op.

de Volkskrant - De twintig mooiste fotoboeken

13.12.2016

Als je het weet, dan zie het, meteen al. Op de eerste pagina's van On the Soft Edge of Space lijkt het alsof ja naar foto's kijkt van een grote, witte tentoonstellingsruimte, met grote foto's aan de muur, maar dat is niet zo. Kijk maar naar de plinten: te poppenhuisachtig. naar de vloer eronder: die sluit net niet helemaal aan. Dit is een maquette, een expositie met kunstwerken op schaal. Wat groot lijkt is in feite van miniatuurformaat. Wat je ziet is niet wat je denkt dat je ziet en dat geldt ook vor het werk van Marleen Sleeuwits (36). Al jaren fotografeert zij uiterst zorgvuldig lege 'non-ruimten', plekken zonder eigen identiteit, zoals vliegvelden en kantoorgebouwen, en altijd vraag je je af: Is dit echt? Door de belichting, de kleuren en de ingrepen die de kunstenaar soms doet (ze bouwt bijvoorbeeld installaties van restmateriaal) doen haar ruimten bijna buitenaards aan. Speciaal voor haar eerste boek bouwde zij een 'white cube'-schaalmodel en richtte het in met kleine afdrukken van haar eigen foto's. Vervolgens fotografeerde ze de minituurtentoonstelling en wisselde die beelden af met grote afdrukken van haar werk zelf. Wat is 'echt' en wat niet-het maakt niet uit. Hier wil je wel even blijven.

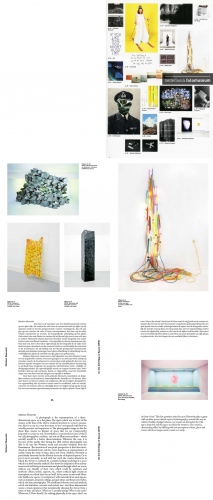

Quickscan catalogue text 2016

Text by Frits Giersberg for the exhibition Quickscan NL #2 in the Nederlands Fotomuseum

A photograph is the representation of a three-dimensional space on a flat plane. The space which was in front of the camera at the time of the shot is rendered in photo in a correct perspective, that is to say in a way that more or less corresponds with how we actually perceive and experience it. The photographic image on the flat plane thus creates an illusion of space that we are (temporarily) prepared to accept as real. Nevertheless (or precisely because of this?) we call photography a realistic, and not an illusionary medium which actually would be a better characterization. Whatever the case, it is because of this quality that during the 19th century photography was able to fit into the Western visual and narrative tradition from the Renaissance. The invention of one-point perspective at that time introduced an absolutely basic rule for every depiction or representation of reality, being the unity of time, place and event. Marleen Sleeuwits is particularly interested in the illusory character of depicted spaces. Or to put it more precisely: in and with her work she creates situations in which the viewer is confused by a realistic looking rendering of a space which is in itself entirely artificial. She draws her inspiration from anonymous work and living environments and places through which we move, without any identity of their own, which could be anywhere and nowhere: offices, hotels, airports, etc., where artificial light creates an atmosphere on which time has no hold. In her more recent work Sleeuwits builds new spaces (or sculptures) with materials from such spaces, such as laminate, dropped ceilings, parquet strips and fluorescent tubes, which she then photographs. The antitheses between real and artificial, actual and imitation, concrete and virtual, two- and three-dimensional create a visual experience that momentarily alienates the viewer from a sense of time and place. What am I actually seeing? What is the scale? Where am I? How should I be relating physically to the space that I see in front of me? This last question arises because Sleeuwits plays a game with another space-related aspect of photography, namely the way in which it builds a bridge between (or creates an alternative for) the space depicted and the space in which the viewer is. She creates a disorienting effect by fiddling with our perception of time, place and event, which no longer seem to exist as a unity.

Nederlandse versie:

Een foto is de weergave van een driedimensionale ruimte op een plat vlak. De ruimte die zich voor de camera bevond ten tijde van de opname wordt in de foto perspectivisch correct weergegeven, dat wil zeggen op een manier die min of meer correspondeert met hoe wij de echte ruimte waarnemen en ervaren. De fotografische afbeelding op het platte vlak creëert dus een illusie van ruimte die wij bereid zijn (even) voor echt aan te nemen. Niettemin (of juist daarom?) noemen wij de fotografie een realistisch en niet een illusoir medium wat eigenlijk een betere typering zou zijn. Hoe dan ook, het is door deze eigenschap dat de fotografie in de 19de eeuw deel kon gaan uitmaken van de westerse beeld- en verteltraditie die ontstond in de renaissance. De uitvinding van het lineair perspectief introduceerde destijds een absolute basisregel voor iedere afbeelding of uitbeelding van de werkelijkheid, zijnde de eenheid van tijd, plaats en gebeurtenis. Marleen Sleeuwits interesseert zich bijzonder voor het illusoire karakter van afgebeelde ruimtes. Preciezer gezegd: in en met haar werk schept zij situaties waarin de beschouwer in verwarring wordt gebracht door een realistisch ogende weergave van een ruimte die op zichzelf geheel kunstmatig is. Zij haalt haar inspiratie uit anonieme, identiteitsloze werk-, verblijfs- en doorgangsruimtes die ogenschijnlijk overal en nergens kunnen zijn. Voorbeelden daarvan zijn kantoren, hotels en vliegvelden, waar het kunstlicht zorgt voor een sfeer waar de tijd geen vat op lijkt te hebben. Voor haar meer recente werk gebruikt Sleeuwits materialen uit dergelijke ruimtes, zoals laminaat, systeemplafonds, lamellen en TL-buizen. Hiermee bouwt ze nieuwe ruimtes en sculpturen, die zij vervolgens fotografeert. De tegenstelling die zij creëertt tussen reëel en artificieel, echt en onecht, concreet en virtueel, vlak en ruimtelijk levert een kijkervaring op die de kijker voor een moment gevoelsmatig losmaakt van tijd en plaats. Waar kijk ik naar? Wat is de schaal? Waar ben ik? Hoe moet ik mij fysiek tot de ruimte verhouden die ik voor me zie? Deze laatste vraag komt op doordat Sleeuwits een spel speelt met een ander ruimte gerelateerd aspect van de fotografie, namelijk de manier waarop deze een brug slaat dan wel een tegenstelling creëert tussen de afgebeelde ruimte en die waarin de kijker zich bevindt. Zij creëert een vervreemdend effect door te morrelen aan onze perceptie van tijd, plaats en gebeurtenis, die niet langer als een eenheid lijken te bestaan.

Review on Monshouwer editions (Dutch only) 2016

Door Saskia Monshouwer

Punt WG is een alleraardigste kunstruimte, gevestigd op het Wilhelmina Gasthuis Terrein in Amsterdam. Misschien moet je even zoeken naar het paviljoen omdat het via een ietwat verwilderde tuin toegankelijk is, maar het loont. In de kleine ruimte met openslaande deuren is bij tijd en wijlen een aardig programma te zien. Tot en met 9 oktober is dat de expositie "Curved Side Down" van Marleen Sleeuwits en Femke Dekkers. Radek Waanja nodigde hen uit om de kleine ruimte te verkennen.

Sleeuwits en Dekker zijn fotograven die het medium om een wonderlijk formele manier gebruiken. Niet als instrument om de werkelijke, eventueel versluierd door strijk- of tegenlicht te verbeelden, maar voor een ruimtelijk onderzoek. Sleeuwits doet dat glanzend. Ze heeft een zekere voorkeur voor soms suikerzoete kleuren. De beelden op de foto spatten je tegemoet. Ze bekleedt de ruimte als het ware met geometrische vlakken, waardoor een lichtend effect ontstaat, dat van grote invloed is op de manier waarop je het beeld en / of de ruimte ervaart. In dat opzicht zet ze de onderzoeken van minimalisten als Dan Flavin en Donald Judd voort die zoals bekend de wisselwerking van mens, kunst en ruimte onderzochten. Dekker gaat heel anders te werk.

Ook Dekker onderzoekt de ruimte, maar zij benut meer klassieke schilderkunstige effecten. Ze gebruikt eenvoudig karton wat met roetzwarte vlekken beschilderd wordt. Het effect is even ruimtelijk, even licht ook, maar refereert veel sterker aan klassieke schilderkunst. Dat wil zeggen aan werk van kunstenaars die verf en kwast hanteren.

Voor degenen die nog regelmatig te maken hadden met schilderkunst en de moderne beschouwingen over de ruimtelijke effecten die een schilder met verf , kwast en spatel kunnen bereiken is wellicht al duidelijk dat wat Sleeuwits en Dekker doen, daar in zeker opzicht de omkering van is. Om op de foto de juiste tactiele en ruimtelijke effecten te bereiken, moeten zij eerst een ruimtelijke installatie bouwen die werkelijk 3D bestaat. De foto maakt de installatie plat. In de schilderkunst werd enkele eeuwenlang precies het omgekeerde nagestreefd. Door de heel verschillende opvatting van kleur en structuur is de samenwerking tussen beide overigens zeer interessant. Het is bijzonder om te zien hoe zij de fijne lichte ruimte op het WG-terrein ervaren hebben. Tot slot nog even over Sleeuwits die naast enkele fotowerken en de installatie ook een prachtige uitgave van Onomatopee in Eindhoven toont. In die ruimte heeft op dit moment ook een solo-expositie .

Curved Side Down‚ Marleen Sleeuwits en Femke Dekkers‚

PuntWG Amsterdam

14-9 t/m 9-10-2016

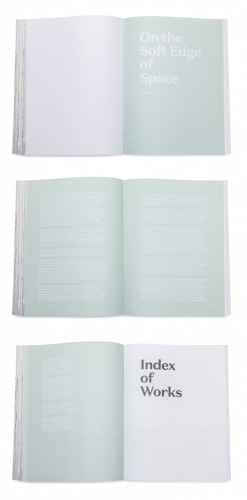

On the soft edge of space 2016

On the soft edge of space

It’s one of the most dramatic opening sequences in film history: two planets slowly align with a glowing orange sun. Accompanying the prologue to 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) is Richard Strauss’ tone poem Also Sprach Zarathustra, a triumphant amalgam of robust copper and potent kettledrums. Strauss named his composition after Friedrich Nietzsche’s ground-breaking philosophical work on good and evil, and humans’ duty to surpass themselves and become ‘superhuman’. However, man has not developed yet in the film’s opening shot. Mankind has yet to evolve from ape to tool-wielding humanoid, to invent technology and eventually set off to explore other planets. Instead there’s only space, endless space. Here, ethics are irrelevant. Human existence is a promise at best.

But even on earth, in locations man-made and physically delineated, there’s no guarantee that space will be anything more than factual. Marleen Sleeuwits has a knack for finding and photographing such non-spaces. Bland hotel corridors, dead corners in office pantries, walled up passageways in the metro system, cavernous service areas – the urban ‘terrain vague’ of the modern age. But naming these scenes would mean identifying them and that’s exactly what Sleeuwits doesn’t do. Instead of titles she bestows numbers on her interiors, cataloguing their anonymity.

The spaces depicted are wholly functionless. Curtains, sockets or air ducts might be identified, but only as forms, not as artefacts referring to any kind of human activity. The available light is unnaturally even, originating from harsh tube lights or industrial halogens. These scenes are completely artificial and utterly self-evident at the same time, in an otherworldly, dehumanised way. They have been conceived and constructed by humans, but seem to be of and for themselves – not unlike outer space as depicted in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Sleeuwits has conducted her search for what she calls ‘in-between spaces’ since 2005. She first makes ‘sketches’ using a small camera, then returns with an 8 x 10 inch for the final, more detailed image. The early works possess a certain architectural quality; one could image walking through this scenery, but probably without consciously noticing it. Over time however, her images became starker, more abstract. Walls and ceilings ceased to be structural elements and became geometric shapes instead. These places exist because of their formal qualities only. Verticals and horizontals interact. Planes collide, contrast and coexist.

These are cognitive black holes and moral blind spots. Our gaze bounces right off – we’re not able to fully grasp what we’re seeing because there’s no point of reference whatsoever. Our emotional response is restricted to a vague form of anxiety, caused by our inability to relate to anything recognisable. We’re unable to grasp the nothingness of it all.

That’s exactly what makes these images so fascinating. Instead of containing and identifying the space - like a picket fence marking the boundary of a garden or a curb telling us where the pavement ends and the street starts - the planes seem to recede. In Sleeuwits’ photographs the edges of space are soft, not in the sense of being out of focus – on the contrary, there’s a level of detail which lends the images an almost glaring clarity – but of being ambiguous. Of course, the walls and ceilings outline a specific volume measuring a specific number of cubic meters. But their lack of characteristics leaves them somewhat transparent. As a result the space itself becomes diffuse.

The year 2011 marked a turning point in Sleeuwits’ work. The artist decided to go beyond merely documenting interiors and start creating them herself. The financial crisis provided a great opportunity as it left dozens of office blocks empty. The first building she worked in was the former home of the rather suitably entitled Stichting Ruimtevaart [the Space Travel Foundation]. Since then, she has moved on to three other locations.

Sleeuwits used to explore the idea of space using purely photographic means – choosing the angle and framing, digitally enhancing the image in post-production. However, as she considers herself more a visual artist than a photographer she felt the creative process had to evolve to a more active, more physical level. Her approach to the office spaces is sculptural. She peels away the wallpaper, lays bare the fluffy insulation material, attacks walls and ceilings with a buzz saw turning them into ‘Swiss cheese’. She turns what once was somebody’s office inside out, strips it, deconstructs it. Then she adds endless strips of aluminium foil, dozens of tube lights and tons of paper tissues to construct a new environment.

The result is truly alienating: it sucks you in and shuts you out at the same time. It forces you to rely on your own devices, traps you inside your head. The cave dwellers in Plato’s famous allegory still had the shadows on the wall to remind them of the world outside the cave; the Greek philosopher’s metaphor for our flawed physical state which makes it impossible to grasp the essence of things, the so-called ‘Ideas’. But here, there are no shadows. Sleeuwits’ caves are perfectly self-contained. There is also no going back to the physical fact. Sleeuwits destroys her creations after photographing them so they only exist as images. They represent the Idea of space itself, an abstraction of an abstraction.

In this book Sleeuwits adds another layer to her work, providing us with one more twist. She has displayed miniature versions of her works in a model of what looks like an elaborate gallery. Picture by picture she walks us through a succession of white cubes. The works gain a physical presence merely by virtue of being hung on a wall, even if it’s a knee-high cardboard reproduction of one. Size matters here and dictates the impact. The smaller, sketch-like photographs appeal to the mind, challenging the eye to glide along edges and shapes. The larger, monumental ones appeal to the body, inviting us to step into the chamber beyond the glass. Within the model these sensations alternate endlessly. There is no exit from this maze, so once again we’re trapped in our own physical shell.

This brings to mind yet another film, Spike Jonze’s feature film debut Being John Malkovich (1999). Its protagonist, a puppeteer named Craig Schwartz who has serious existentialist doubts, accepts a job at a mysterious firm called Lester Corp. When he reports to head office in Manhattan, he is directed to the five-foot high, seventh-and-a-half floor. Painfully aware of the physical limitations Schwartz finds a way out behind a cabinet: a hidden door acts as a portal into actor John Malkovich’s brain. However, after 15 minutes, he is ejected into a ditch along the New Jersey Turnpike – a non-descript place if there ever was one – and left to his own musings all over again.

There is no such redemption – pseudo or not – in Sleeuwits’ world. We are forever in limbo, trying to grasp the unthinkable. Or maybe there is some hope. As of late Sleeuwits has moved into three-dimensional media, producing sculptures from the same base materials she uses to create her eerie mind traps. She ties together coloured lights and electrical cords, wraps tiles in tin foil making them look like monstrous chocolate bars or inexplicable Space Shuttle parts, stacks blocks of Styrofoam and goes haywire with Sellotape. The sculptural references are clear - Carl André, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd – and sculptural is what these works are. Sleeuwits has moved from depicting environments, capturing the idea of space on the flat surface of a photograph, to placing objects in space. Not only has the process of creation become physical and active, so has the result. These sculptures communicate in a more direct way than the photographs, which are inherently transitive. Still, when combined with the photographs in an installation some of that directness seems to rub off on the two-dimensional works. The sculptures are tactile and real, inviting us to touch and smell, to experience on a less cerebral level. But they are artificial nonetheless. They are strangely attractive and forbidding at the same time. In a way they represent space folded in on itself, locking us out while promising a way in.

Edo Dijksterhuis

Fotomagazin 2014

Â

The Transparency of Appearance 2010

On (the work of) Marleen Sleeuwits

By Mischa Andriessen

To get people to look twice at something they pass by every day: for the Russian writer Victor Shklovsky, this modest objective was the very pinnacle of what he could achieve as an artist. There is a lot – both beautiful and ugly – that a person passes by without noticing – because his thoughts are somewhere else, because he is not observing, but only looking in a limited way: enough to avoid tripping or running into something and not much else.

However, what you can also be sure of is that on a daily basis, you pass by a lot of things that – to put it euphemistically – do not beg closer observation. Many buildings have been erected on purely practical principles. Their functionality is connected to their lack of personality, or their ability to constantly adopt a new identity. Ceiling systems, sliding partitions, wheeled tables and chairs: everything can be adapted to the taste and requirements of the temporary user of the space. As soon as he leaves the space, there is a lightning-fast scene change and the next user will not or will hardly be aware of the previous use of the space. While the space itself may age, the walls do not absorb anything of the lives that have played out between them – in contrast with, for example, old homes.

The increasing separation of living and working has led to urban areas where at certain times one can hardly find a living soul. Residential neighbourhoods where during the daytime everyone has gone to work, where there are no older people and where the children have been brought to the crèche; areas like the WTC in Amsterdam, which has a high concentration of corporate buildings – bustling during the daytime, but outside office hours, for instance on Sundays, completely deserted – or places where everyone is in transit, like the railway stations and bus terminals in commuter towns like Zoetermeer, or airports across the world: those who are in these areas, only want to be there temporarily.

The Hague photographer Marleen Sleeuwits seems fascinated by such areas of transit: places where people only stay for a short period of time. They are places that do not need to be seen – preferably not, you’d almost think, until you see Sleeuwits’ photos.

In these images, people have disappeared, and it seems as if only then do you understand the architect’s concept: a symmetry becomes visible, or a different play of forms. Stark lines, strict lines, which reveal sophisticated patterns – much less casual than you thought. Now that nobody’s walking through the picture, there are no coats hanging on the wall or bags lying around, the space acquires a kind of abstract beauty.

The work titled ‘Interior No. 15’, for example. A large expanse of yellow wall, which together with the rigid geometry of the square floor tiles, the austere white lines of the ceiling frames and even the exemplary symmetry of the nozzles of the fire sprinkler system, displays a well-considered and compelling formal interplay.

Nevertheless, this is not the essence of Sleeuwits’ work. Her work is not architecture photography, offering the viewer a second, more concentrated view of that which previously escaped him. Sleeuwits sooner makes portraits of buildings; of buildings that do not immediately reveal their identity or indeed seem to lack one altogether. As portraits, the photographs resemble those made on very rare occasions of seasoned models or media icons: when the photographer manages to penetrate the façade; reach the core of his subject.

In ‘Interior No. 15’, the yellow wall plays a crucial role, because it is not immediately clear whether it is reflective or, on the contrary, transparent. A concentrated second viewing contributes to the suspicion that there is a space behind this yellow wall. There are doors or walls on opposite sides, but there’s not much else to be seen; nothing to say about this space. It is precisely the ‘revealing’ of this area behind the wall that increases the mystery of this space and consequently of this photo. What are we looking at? Where are we? There are no clues to help us determine what kind of building we are looking at, what kind of space, in which country and at which hour.

Sleeuwits records the alienation of such non-places. It’s possible that it’s not the ugliness of many of such locations that has us fleeing the area – because these and other places photographed by Sleeuwits do have a certain beauty (not charm – beauty): it’s their impersonality, their intention to exclude and to avoid contact, that repels us. They are locations that do not wish to be known.

Take the ink black windows in the bright yellow wall in the picture ‘Interior No. 14’. It could be an underground station, but it is entirely deserted and the floor is all too clean. It is precisely these shining tiles and windows, the reflection of colourful lamps and the freshly scrubbed floor that lend this space its unreal atmosphere. The appearance of transparency.

Take ‘Interior No. 11’, with the large rectangular window, behind which a dark blue light illuminates a hallway or a narrow room, which, with its net curtain and two spotlights that shine brightly like a pair of eyes, evokes an almost sinister kind of tension.

The photographs do not visibly strain after effect to achieve this tension. There is no play of shadows, suggesting that there is life in the space after all. Sleeuwits’ photos are far removed from horror film stills. It is the complete matter-of-factness of the portrayed spaces that creates this tension – their invulnerability. It is tempting to say that a building without people has no soul. That’s not the issue – no, that is precisely the issue. That’s it exactly: soulless and nevertheless extremely seductive.

In her artist’s statement, Sleeuwits had the following to say on this matter: ‘The photographs that I take are the result of an investigation of my state of disconnection from the space I am in. A conflicting feeling that certain spaces and locations in the urban environment evoke in me. It is as if you are separated from the actual spot, but at the same time experience the beauty of this spot.’

This ‘state of disconnection’ is essential. In the same statement, Sleeuwits talks about a ‘claustrophobic atmosphere’ and an ‘eerie feeling’. In the artist’s words, she experiences both on a daily basis and in a multitude of locations. It is this experience that she records in her photographs and which she connects to the search for what she herself calls ‘magical beauty’. Sleeuwits is not concerned with making an authentic record of a particular space. The photographed object is only a ‘found object’ to a limited extent. Yes, Sleeuwits is constantly on the lookout for suitable locations, scouring buildings in search of a location that offers an opportunity to actually combine the two qualities that she aims to connect to one another. As in fashion photography, the image is staged, photoshopped, retouched, until the sought-after balance between orderly and illogical, recognisable and intangible, attractive and repulsive has been achieved.

By adopting a meticulous approach to her prints, making clever use of the available (artificial) light and by carefully considering the presentation form, Sleeuwits manages to achieve what she hopes to accomplish. This technical aspect of her work characterises her commitment and professionalism, but does not explain the mysterious allure of her photographs, other than that this attraction is no coincidence, but is purposively realised by the photographer.

This mystery is located in the space’s soullessness; in this depiction without reservations of a lack of personality. ‘Interior No. 5’ is a good example of such an intriguing, identity-less space. A marble floor, a wall covered in mosaic tiles in a range of grey tones, fuse boxes, a grey office table with a crooked leg shoved against the wall to the right, a large door in the wall on the left that is raised a whole section up from the floor and has heavy silver fittings. Above the door is a white box with something red in the middle – is it an alarm? The door – is it the door of a safe, a vault? The unreal atmosphere is intensified by the bright white lamp high up on the left wall: its light falls in an orderly diagonal across the back wall and throws a sharp triangle of shadow on the space below the table. This table has clearly been placed to the side of the room. Perhaps unusable due to its crooked leg, it has been placed so it stands as little in the way as possible. The fact that it has been removed as far as possible from the door suggests that the way through needs to stay clear; that someone always needs to be able to reach it. Whether this happens very often remains to be seen. This does not seem a space that is regularly visited – just look at the ceiling where worn patches and moisture stains leave the impression that it has been quite some time since someone has taken care of this spot.

Marleen Sleeuwits’ photographs are mysterious, but they are not riddles. There is no answer. They immediately inspire the question where and when they were made, but even while wondering this, one immediately knows that the question is pointless, because the answer will take away none of the mystery. Sleeuwits’ photographs confirm the imperfection of how we view things, but what they do even more is confront us with our search for a handle. They show that knowledge often stands in the way of observation. Sleeuwits’ photographs are an intensified gaze, a second glance – viewing in such a way that there is no need for understanding, or rather, order is restored again: viewing comes before understanding.

De transparantie van schijn

Over het werk van Marleen Sleeuwits

Door Mischa Andriessen

Mensen een tweede keer laten kijken naar datgene waaraan ze dagelijks voorbijlopen; de Russische schrijver Victor Sjklovski zag dat bescheiden doel als het hoogste wat hij als kunstenaar kon bereiken. Er is veel – mooi én lelijk- dat aan een mens voorbijgaat, omdat hij met zijn gedachten elders is, omdat hij niet waarneemt, maar slechts met mate kijkt; genoeg om niet te struikelen of ergens tegenaan te botsen en niet meer dan dat.

Het is echter ook zeker zo dat een mens dagelijks het nodige passeert dat er, om het eufemistisch te zeggen, niet om smeekt te worden bekeken. Veel gebouwen zijn vanuit een louter praktische grondslag neergezet. Hun functionaliteit hangt samen met hun gebrek aan persoonlijkheid ofwel hun vermogen om telkens een andere identiteit aan te nemen. Systeemplafonds, schuifwanden, verrijdbare tafels en stoelen; alles kan worden aangepast aan de smaak en behoeften van de tijdelijke gebruiker van de ruimte. Zo gauw deze het vertrek verlaat, vindt er een razendsnel changement plaats en de volgende gebruiker zal niet of nauwelijks iets merken van het eerdere gebruik. Het vertrek wordt misschien wel ouder, maar anders dan bijvoorbeeld in oude huizen zuigen de muren niets van het leven dat er heeft plaats gevonden in zich op.

Doordat wonen en werken meer en meer gescheiden worden, ontstaan er ook stedelijke gebieden waar op bepaalde tijden nauwelijks nog iemand is. Woonwijken waar overdag iedereen uit werken is, waar geen oudere mensen wonen en waar de kinderen naar de crèche zijn gebracht; plekken als het Amsterdamse WTC waar een grote concentratie bedrijven bijeen zijn gezet, waar het overdag een drukte van belang is, maar die buiten werktijd, bijvoorbeeld op zondag, volledig uitgestorven zijn; of plaatsen waar iedereen op doorreis is als de trein- en busstations in forensensteden als Zoetermeer of vliegvelden waar dan ook: wie er is, wil er maar even zijn.

De Haagse fotografe Marleen Sleeuwits lijkt gefascineerd door dergelijke doorgangsplekken; plaatsen waar mensen zich altijd maar kort ophouden. Het zijn plekken die niet gezien hoeven te worden, liever niet, zou je haast denken, tot je Sleeuwits’ foto’s ziet.

In die foto’s zijn de mensen verdwenen en het heeft er de schijn van dat je dan pas de idee van de architect begrijpt; er wordt een symmetrie zichtbaar of een andersoortig vormenspel. Strakke lijnen, strenge lijnen, die geraffineerde patronen aan het licht brengen, veel minder achteloos dan je dacht. Nu er niemand doorheen loopt, er geen jassen hangen of tassen rondslingeren, krijgt de ruimte een abstract soort schoonheid.

Zoals het werk dat werd getiteld “Interior No. 15â€. Een grote gele wand die in samenspraak met de rigide geometrie van de vierkante vloertegels, de strakke witte lijnen van de plafondlijsten en zelfs de voorbeeldige symmetrie van de sprinklerknoppen van de blusinstallatie, een doordacht en dwingend vormenspel toont.

Toch is dat niet de kern van Sleeuwits werk. Het is geen architectuurfotografie die de kijker een tweede, betere blik gunt op wat hem is ontgaan. Sleeuwits maakt eerder portretten van gebouwen; van gebouwen die hun identiteit niet direct prijsgeven of er zelfs geen lijken te hebben. Het zijn portretten zoals die heel soms van doorgewinterde modellen of media-iconen worden gemaakt; de fotograaf weet dan door te dringen tot achter de façade, waar het wezenlijke zich ophoudt.

In “Interior No. 15†is de gele wand cruciaal omdat niet meteen duidelijk is of deze spiegelt of juist doorschijnend is. Een geconcentreerde tweede blik voedt het vermoeden dat zich een ruimte achter deze gele wand bevindt. Aan weerszijden zijn er deuren of ramen, verder valt er niets te zien, niets over deze ruimte te zeggen. Juist door het ‘prijsgeven’ van die ruimte achter de wand wordt het mysterie van deze ruimte en daarmee van deze foto alleen maar groter. Waar kijken we naar? Waar zijn we? Er zijn geen aanknopingspunten om vast te stellen naar wat voor gebouw we kijken, naar wat voor een ruimte, in welk land en op welk tijdstip.

Sleeuwits legt de vervreemding van dergelijke non-plekken vast. Het is misschien niet de lelijkheid van veel van dergelijke locaties die ons op de vlucht doet slaan, want deze en andere door Sleeuwits gefotografeerde plekken, hebben wel degelijk hun schoonheid (niet charme; schoonheid); het is hun onpersoonlijkheid, hun intentie om buiten te sluiten en contact te vermijden, die afstotend werkt. Het zijn plekken die niet gekend willen worden.

Neem de diepzwarte ramen in de felgele muur op “Interior No. 14â€. Het zou een metrostation kunnen zijn, maar het is volledig verlaten en de vloeren zijn wel heel voorbeeldig schoon. Juist die glimmende tegels en ruiten, de weerspiegeling van kleurige lampen en de schoongeboende grond, geven deze ruimte zo’n onwezenlijke sfeer. Een schijntransparantie.

Neem “Interior No. 11†met dat grote rechthoekige raam waarachter in een donkerblauw licht een gang of een smal vertrek zichtbaar wordt dat door de vitrage en de twee spots die als twee ogen fel oplichten, een bijna sinister soort spanning oproept.

Die spanning is niet het gevolg van een zichtbaar effectbejag. Er is geen spel met schaduwen dat toch ergens leven doet vermoeden. Sleeuwits’ foto’s zijn bepaald geen stills uit horrorfilms. Het is het volkomen vanzelfsprekende van de geportretteerde vertrekken dat die spanning te weeg brengt, hun onaantastbaarheid. Het is verleidelijk om te zeggen dat een gebouw zonder mensen zielloos is. Dat is het niet, nee, dat is het juist wel. Precies dat is het: zielloos en desondanks zeer verleidelijk.

Sleeuwits zei daar in haar artist’s statement het volgende over: ‘De foto’s die ik maak zijn het resultaat van een onderzoek naar het niet verbonden zijn met de ruimte waarbinnen ik mij bevind. Een conflicterend gevoel dat bepaalde ruimtes en plekken in de stedelijke omgeving in mij oproepen. Het is alsof je losstaat van de werkelijke plek, maar tegelijkertijd ook de schoonheid van deze plek ervaart.’

Dat ‘niet verbonden zijn’ is essentieel. In datzelfde statement heeft Sleeuwits het over ‘claustrofobische sfeer’ en ‘unheimisch gevoel’. Beide ervaart ze naar eigen zeggen dagelijks en op veel plaatsen. Het is die ervaring die ze in haar foto’s vastlegt en die ze verbindt met de zoektocht naar wat zijzelf ‘magische schoonheid’ noemt. Het gaat Sleeuwits niet om het op een authentieke manier vastleggen van een ruimte. Het gefotografeerde is maar in beperkte mate een object trouvé. Ja, Sleeuwits speurt voortdurend naar geschikte locaties, schuimt gebouwen af op zoek naar een plek die de mogelijkheid biedt de twee kwaliteiten die zij aan elkaar wil koppelen, daadwerkelijk met elkaar te verbinden. Net als bij modelfotografie wordt er geënsceneerd, gephotoshopt, geretoucheerd; net zo lang tot het gezochte evenwicht tussen ordentelijk en onlogisch, tussen herkenbaar en ongrijpbaar, tussen aansprekend en afstotend, is bereikt.

Door heel precies te zijn bij het afdrukken, uitgekiend gebruik te maken van het aanwezige (kunst)licht en door heel zorgvuldig de presentatievorm af te wegen, bewerkstelligt Sleeuwits wat zij nastreeft. Dat technische aspect van haar werk tekent haar toewijding en professionaliteit, maar verklaart de mysterieuze aantrekkingskracht van haar foto’s niet, anders dan dat deze niet een toevalligheid is, maar iets dat door de fotograaf wordt gerealiseerd.

Dat mysterie huist in de zielloosheid, in dat vertoon zonder voorbehoud, van een gebrek aan persoonlijkheid. “Interior No. 5†is een goed voorbeeld van zo’n intrigerende identiteitsloze ruimte. Een gemarmerde vloer, mozaïektegeltjes aan de muur in verschillende grijstinten, stoppenkasten, een grijze kantoortafel met een scheve poot rechts tegen de muur geschoven, in de muur links een grote deur die een heel stuk boven de vloer begint en met een groot zilveren beslag. Erboven hangt een witte doos met iets roods in het midden, is het een alarm? en is de deur dan de deur van een brandkast, een kluis? De onwezenlijke sfeer wordt versterkt door het heldere witte licht helemaal linksboven; het schijnsel valt in een strakke diagonale baan over de achterwand en werpt een scherpe driehoekige schaduw op de ruimte onder de tafel. Die tafel is duidelijk aan de kant gezet. Misschien onbruikbaar door die scheve poot is hij zo geplaatst dat hij zo min mogelijk in de weg staat. Doordat hij zo ver mogelijk van de deur verwijderd is, wordt de suggestie gewekt dat die doorgang vrij moet blijven, dat er altijd iemand bij moet kunnen. Of dat vaak gebeurt, valt te betwijfelen. Dit lijkt geen ruimte waar geregeld iemand komt, kijk naar het plafond waar slijt- en vochtplekken de indruk wekken dat het wel even geleden is dat iemand zich over deze plek heeft ontfermd.

De foto’s van Marleen Sleeuwits zijn mysterieus, maar het zijn geen raadsels. Er is geen uitkomst. Ze roepen onmiddellijk de vraag op waar en wanneer ze zijn gemaakt, maar de vraagsteller weet ook meteen dat die vraag zinloos is omdat het antwoord niets van het mysterie wegneemt. Meer nog dan dat Sleeuwits’ foto’s ons gebrekkig kijken bevestigen, confronteren ze ons met ons zoeken naar houvast. Laten ze zien dat dikwijls het weten het kijken in de weg staat. Sleeuwits’ foto’s zijn een geïntensiveerde blik, een tweede blik – zo kijken dat het begrijpen overbodig wordt, of beter gezegd, de orde weer wordt hersteld; de blik komt voor het begrip.

Review Artforum 2009

Exhibition 'Transformations' in MKgalerie Berlin

By DANIEL BOESE

Sometimes it is hard to see the crisis that you are in. Everybody in Berlin seems to be worrying about how many of the city's 450 galleries will be closing and which big players will go. Meanwhile, at one of the smaller and fairly new spaces, the Berlin outpost of Rotterdam-based MKgalerie, one could see dispatches from the environmental and social crises around the globe. Trans- formations" did what commer- cial group shows seldom do: It carried a genuine curatorial message. Pirn Palsgraaf's three installations were made of taxi- dermied animals and found materials, resulting in works like Multiscape 10, 2009, where a building resembling an oil platform towers over an elephant's foot - technology dominating nature. The photographer Xing Danwen showed the series "Urban Fiction," 2004-, pictures of Chinese real estate models into which she had Photoshopped herself as a tennis player or as a victim of domestic violence. Xing has created powerful images of a lifestyle, where one has difficulty discerning which is more fantastic: the artist's creative self-portraits or the dream of exporting an unsustainable, even potentially brutal lifestyle to everyone on the globe.

Of all the works on view in "Transformations," however, "Interiors," 2007-, a series of images by Dutch photographer Marleen Sleeuwits, delves most deeply into the question of what is wrong with the contemporary economy. There is not much to see in Sleeuwits's photographs. People are absent, and the scope of the images leaves room for only a few details: a folded curtain, the railing of a staircase, the corner of a hallway. What lures the viewer into these architectural interiors is their luminous glow. A linoleum floor colored like blue marble shimmers like a pool; a collection area for cafeteria trays lets a ray of neon brightness escape into a dark hall; the lighting of a hallway turns its walls into a pastel yellow.

Sleeuwits is a chronicler of non-places, those spaces created by functionalist architecture that we use daily but seldom notice: hallways in office buildings, government agencies, or metro stations; storage rooms; cafeterias. The French anthropologist Marc Auge coined the term to refer to spaces without any relation to human history. Working with available light only-contrary to expectation, this does not create harsh shadows and cold colors but glossy colors and surfaces-Sleeuwits focuses on the details of these non-places, on the textures of ceiling tiles, carpets, and curtains, and most prominently on their light.

It is in this gloss that the ambivalent core of her work lies. No glasses, books, or bags are left lying around. Not even the anonymous traces of wear and tear can be seen: no scratch marks on the corners, no spots on the floor, no cracked tiles or crooked doors. The results are images of alienation. Rather than the empty museums and libraries in Candida Hòfer's photographs, which despite their desolation echo the accumulation of cultural knowledge and capital, Sleeuwits's images find only the rationalized vision of human work and life as seen by corporate architecture firms. The uncanny anonymity of these places may echo that of the photographic crime scenes of Thomas Demand, but these are not settings of spectacular atrocities or great political intrigues. Instead, Sleeuwits's buildings are those intended to be cheerful and inviting; they become eerie, anonymous, and depressing because of the way they disconnect their inhabitants from the natural world. No natural light, no relation to place, humans reduced to happy drones: a pretty disaster.

Dagblad van het Noorden 2005

Door Issabella Werkhoven

In de starters-expositie-ruimte De Permanente is ditmaal een een trio-tentoonstelling ingericht met jonge fotografen. Pieter Numan, Marleen Sleeuwits en Ine Boermans maken alledrie werk waarin de leegte domineert. Die leegte wordt spijtig invoelbaar als blijkt dat het enige werk van Ine Boermans, een videoprojectie, defect is. Er blijven dus nog maar twee exposanten over.

Piet Numan maakt heel grote foto's van stukken stad bij lantaarnlicht. Het zijn een beetje tussenplekken; een stoep omzoomd door bomen, een gedeelte van een spoorwegovergang bij een stationnetje. Van afstand trekken ze aan door de kleur maar bij nadere beschouwing willen ze te graag inponeren. Het afgebeelde maakt de grote formaten niet waar, want het is niet bijzonder genoeg. Numan vertrouwd iets te gemakkelijk op het effect van de nachtelijke duisternis en de lantaarn als volgspot.

Collega Marleen Sleeuwits doet het beter met minder. Zij toont twee uitgebalanceerde series op een bijna vierkant formaat van zo'n 50 x 45 centimeter. Sleeuwits zegt gefascineerd te zijn door de 'overvormgeving' van de gecultiveerde wereld om ons heen. "Alsof je in een verbeterde versie van de werkelijkheid bent terechtgekomen", vindt ze. Ze wordt afwissend aangetrokken en afgestoten door die perfecte opgepoetste schoonheid. Dat is te zien in haar foto's, waarin ze de perfectie op haar beurt weer perfect in beeld brengt. Licht kleur en compositie zijn uiterst nauwkeurig op elkaar afgestemd.

De geénsceneerde serie, waarin perfecte mensen figureren in hun hagelwitte appartementen, is inhoudelijk het minst interessant omdat de ambivalentie hier niet zichtbaar is. Het zou evengoed een fraaie reclamecampagne kunnen zijn voor een parfum. Pas in de fotoserie met uitsnedes straathoeken, vliegveld toiletten en pleinen wordt die perfecte leegte schrijnend, want desolaat. Eenzaam.

Één foto toon teen schriel boompje, ingekapseld door het trottoir, tegen de glanzend muur van een fancy kantoorgebouw waaraan een aantal draden feestverlichting zijn gemonteerd. Het boompje laat het gedwee over zichheen komen. Intussen speelt Sleeuwits een geraffineerd spel met reflecties die behalve bijdragen aan de compositie, ook iets onthullen van wat er zich buiten ons blikveld bevindt. Gevolg hiervan is dat de foto's van Sleeuwits een vervreemdende, doodstille schoonheid bezitten. En als toeschouwer neem je klakkelos aandat dit werk zo gemaakt moest, op dit formaat, in deze uitsnede en niet anders.