Video portrait by the Centre Photographie Rouen Normandie

https://vimeo.com/865649684

Review in French newspaper Libération

(In French, Underneath is a translated version)

Urbain a Remous

Exposée au Centre photographique de Rouen, l'artiste s'intéresse à la «peau des villes» en explorant l'aspect sculptural de son médium.

Comme dans un conte fantastique, où une dimension s'ouvre sur une autre, le fascinant labyrinthe de Marleen Sleeuwits brouille nos repères visuels... Au Centre photographique de Rouen, l'artiste néerlandaise se joue de nos perceptions avec des photographies dont il est difficile de déterminer le sujet, l'histoire mais aussi la notion d'espace. «J'essaye d'élargir la photographie, pour en re-pousser ses limites. Mes installations sont comme des photos dans lesquelles on peut entrer», explique-t-elle la veille de l'ouverture. «Je travaille sur la peau des villes», ajoute l'artiste, née en 1980 et formée à Royal Academy of Art de La Haye.

C'est en louant un immeuble pour une somme modique dans la ville néerlandaise, après la crise financière de 2008, que l'artiste plonge dans la dimension expérimentale et sculpturale de son médium. Là, elle dépouille le lieu, arrache les faux plafonds, décortique les néons, prélève l'isolant, puis réas-semble ces résidus en com-positions qu'elle photographie. Elle redonne une seconde vie à ces matériaux négligés. «J'ai commencé à faire une sculpture puis je me suis dit, mais je suis photographe, que vont penser les gens ?J'avais compris que certaines choses étaient mieux en plusieurs dimensions.» Dans ses photographies, murs, tuyaux, poutres, briques, néons se transforment en ovnis visuels avec une palette pastel et acidulée. Pour perdre un peu plus le regard, l'artiste n'hésite pas à peindre des confettis ou des formes géométriques sur ses tirages. Elle y colle aussi de vrais papiers en relief ou des gouttelettes en verre.

Issues d'une résidence à Rouen, ses dernières images ont pour point de départ les carrières de craie, les grottes et les églises de la ville. Dans son studio à La Haye, elle a retravaillé les images, brûlé ses tirages. Puis elle a déplié les couches de l'épiderme rouennais en imprimant ses photos sur de la pierre. Elle a aussi moulé un morceau de l'abbatiale Saint-Ouen pour en faire une sculpture de plâtre, telle une photographie en trois dimensions. Comme par magie, la peau blanche de Rouen mute alors en nervures, squames et méandres encéphaliques. Et non, Marleen Sleeuwits n'a pas vandalisé une cathédrale avec un spray en couleur! C'est dans son studio que la couleur orange est apparue, grâce à du bois, à travers des gélatines transparentes. Ou-verte à la sérendipité, la photographe est passée maîtresse en l'art de la transsubstantiation optique.

CI.M. (à Rouen)

«IN SITU» de MARLEEN SLEEUWITS au Centre photographique Rouen Normandie, jusqu'au 6 janvier 2024.

Urban Bubblebath

Exhibited at the Centre Photographique in Rouen, Marleen Sleeuwits is interested in the "skin of cities", exploring the sculptural aspect of her medium.

As in a fantastic tale, where one dimension opens onto another, Marleen Sleeuwits' fascinating labyrinth blurs our visual reference points... At the Centre Photographique de Rouen, the Dutch artist plays with our perceptions with photographs whose subject, history and notion of space are difficult to pin down. "I try to expand photography, to push its limits. My installations are like photos you can enter," she explains on the eve of the opening. "I work on the skin of cities," adds the artist, born in 1980 and trained at the Royal Academy of Arts in The Hague.

It was when she rented a building in the Dutch city for a modest sum, after the financial crisis of 2008, that the artist plunged into the experimental and sculptural dimension of her medium. There, she strips the place bare, rips out the false ceilings, deconstructs the neon lights, removes the insulation, then reassembles these residues into compositions that she photographs. She gives a second life to these neglected materials."I'd started to make sculptures and then I said to myself, but I'm a photographer, what are people going to think? I'd realized that some things are better in several dimensions. In her photographs, walls, pipes, beams, bricks and neon lights are transformed into visual UFO’s using a pastel and acid palette. The artist doesn't hesitate to paint confetti or geometric shapes on her prints, to make them a little less eye-catching. She also glues real paper in relief or glass droplets.

Born of the residency in Rouen, her latest images take the city's chalk quarries, caves and churches as their starting point. In her studio in The Hague, she reworked the images and burnt her prints. Then she unfolded the layers of Rouen's skin by printing her photos on stone. She also moulded a piece of the Abbey of Saint-Ouen into a plaster sculpture, like a three-dimensional photograph. As if by magic, the white skin of Rouen is transformed into veins, scales and brain meanders. And no, Marleen Sleeuwits did not vandalize a cathedral with a coloured spray! It was in her studio that the colour orange appeared, using wood and transparent gelatin. Open to serendipity, the photographer has mastered the art of optical transubstantiation.

CI.M. (in Rouen)

“IN SITU" by MARLEEN SLEEUWITS at the Centre photographique Rouen Normandie, until 6 January 2024.

Interview by Yale Radio

https://museumofnonvisibleart.com/interviews/marleen-sleeuwits/

Kunst is Lang

One hour interview in Dutch

11 mei 2021

https://podhub.nl/podcasts/kunst-is-lang-en-het-leven-is-kort/aflevering-168-marleen-sleeuwits/

Palet 398 - dec/jan 2018

Een beetje manisch

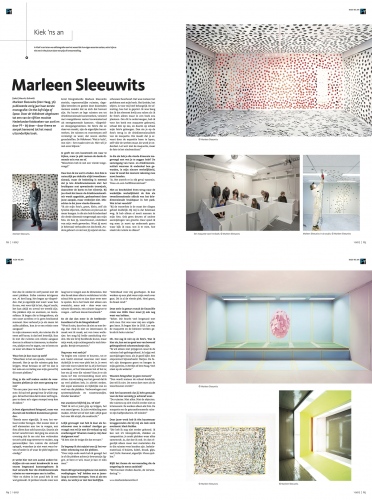

Extreem? ‘Ik niet bijvoorbeeld een ruimte volledig vol met papieren handdoekjes – weken werk! – of boor 3000 gaten in een systeemplafond. Het moet altijd een beetje manisch zijn, dat hoort bij mijn werk,’ vertelt ze lachend. De stap om achter de camera vandaan te komen, en ook de rol van beeldhouwer, architect of schilder aan te nemen, voelde in eerste instantie groot. ‘Ik was niet gewend om, naast foto’s, zelf iets te maken. Maar ik wilde meer eigenheid in mijn beelden leggen.’ Voor vijftig euro per maand huurde ze een halfjaar lang een lelijk leegstaand kantoorpand. ‘Daar kon ik uit mijn eigen systeem komen en dingen uitproberen.’

Smoel

Zo ontstond al experimenterend een speelse eigen beeldtaal, waarmee Mar- leen de gekozen ruimte smoel geeft. Nog steeds is de plek niet te plaatsen,

wel is hij verheven uit zijn non-status. Iso- latieplaten, tl-buizen, glaswol en andere op de locatie aangetroffen materialen schitteren in hun nieuwe rol: ze bedek- ken, vullen, bepalen en vervormen de ruimte. Kleine aanwijzingen, zoals een stopcontact of een snoer, plaatsen de vervreemdende setting terug in de reali- teit en maken van haar foto’s ook zoek- plaatjes. Hoewel de fotografie nog maar een klein onderdeel van het maakproces is, draagt de kwaliteit van de beelden bij aan dat aspect: ‘Mijn foto’s zijn belache- lijk scherp.’ En naast foto’s zijn er inmid- dels ook op zichzelf staande installaties en sculpturen van haar hand.

Marleen is in de loop der jaren op de meest uiteenlopende locaties terechtge- komen. ‘Ik kies een plek, bij voorkeur een stad met veel leegstand, en daar bezoek ik dan voormalige ziekenhuizen, universiteiten of kantoorpanden.’ Welke plek haar het meest is bijgebleven? ‘Een verlaten mortuarium was heel creepy. Maar een echt Being John Malkovich- moment had ik in een gebouw waar ik al een jaar mijn atelier had. Ik ontdekte een smal deurtje, dat je alleen kon openen door je vinger in een gaatje te haken. Vanaf de richel erachter kon je bovenop het systeemplafond kijken. De achter- kant van een ruimte, voor mij was dat de jackpot!’

Inception

Een nieuwe stap in haar werk is herge- bruiken wat de ruimte al heeft. Daarbij doet zich een soort Droste-effect voor: elementen worden gefotografeerd en opnieuw in de ruimte geplaatst. Als het patroon van de vloer terugkeert als muur en tl-buizen zowel fysiek als in print wan- den en plafonds bedekken, doet dat iets geks met je perceptie. Een Inception- achtige (de film van Christopher Nolan uit 2010) kijkervaring. Zo ook haar site-spe- cific werk in een cel in de Haarlemse koepelgevangenis, waar ze zich 24 uur lang liet opsluiten. ‘Heerlijk leek me dat: even tijd voor mezelf, een boek lezen. Maar dat viel tegen. De plek en zijn ge- schiedenis zijn beklemmend, je voelt daar de zwaarte.’ Voor wat speels te- genwicht verfde ze de hele cel blauw, in- clusief vloer en toilet. Met prints van ter plekke gefotografeerde buizen bedekte ze de muren. Een tijdelijke metamorfose voor een plek in transitie.

Omgekeerde wereld

Zo verheft Sleeuwits non-plekken tot unica. De kortstondigheid van de trans- formatie versterkt dat nog eens: grote kans dat je de gefotografeerde locatie nooit in het echt zult zien of herkennen. Tegenwicht voor overbekende trekpleis- ters, die intussen door de mensheid de afgrond in worden gefotografeerd. Na miljoenen uitwisselbare foto’s verworden

Frame Magazine N0.127 MAR - APR 2019

Text: JANE SZITA

Portraits: MICHÈLE VAN VLIET

So you’re a photographer who spends

more time creating spaces than shooting pictures . . .

You mean because your interiors are partly composed of photographs? That’s part of it. As you can see in my site-specific installation in Toronto, where photos of the floor become the wall and vice versa, you always have to ask yourself: what’s the photo, and what’s the installation? It’s completely blurred. I like that.

You’re giving us a puzzle to solve – but why?

It’s my personal translation of how I experi- ence these spaces. I’m asking what it is that surrounds us. How do we relate to our environment? I play with those ideas. It’s my own interpretation of space.

How do you convey your interpretation to the audience? I use an 8x10 camera, which gives enormous detail. You can see specks of dust, flecks of paint. It’s very tactile. I present each photo on a monumental scale, as if it were a window. Lately, I’ve made the photos freestanding – like a wall, they make a kind of 3D space. The viewer enters into it.

You started with a fascination for found spaces that are pretty much non-spaces.

I like to play with scale, without using giveaways – no people, no furniture, no doors. I might include a few small clues, like wall sockets.

Lately, your photos of places feature photos of those same places. What’s going on?

What effect are you looking for?

When it all comes together, the result can be magical. Sometimes it takes a week, sometimes longer, and sometimes it doesn’t happen at all.

What’s your goal as an artist?

You also photograph interiors for Volkskrant Magazine. What , if anything, do those shots have in common with your other work? I’d say my style comes through in everything I do. It’s clean and static. It feels natural. What you see is what you get.

You work with an analogue camera. How do you feel about digital photography?

What inspires you? Among many other things, DIY stores, architects’ models, and the work of people like Canadian photogra- pher Lynne Cohen. She influenced my ideas about photos as objects.

Do you study the audience’s reaction to your work? As my recent project in Toronto was in a public space, I was able to hang around a lot and observe people. They took lots of selfies with my piece. I like that; there’s a certain irony to it. I think there’s more than one way into my work, and that’s a good thing. People can enjoy it on a visual or a conceptual level.

You recently made a book about your work,The Soft Edge of Space. It doesn’t look quite like the average monograph.

a ‘model’ sticker to the book cover. â—

Hard Hoofd

Click here to listen to the complete interview (in Dutch).

https://soundcloud.com/hardhoofd/ondercast-marleen-sleeuwits

PF Magazine, February Issue 2017

HOUVAST EN VERWONDERING IN VERVREEMDING

MARLEEN SLEEUWITS

tekst Maurits Schmidt

Marleen Sleeuwits (Den Haag, 36) publiceerde vorig jaar haar eerste monografie: On the Soft Edge of Space. Door de Volkskrant uitgekozen tot een van de vijftien mooiste Nederlandse fotoboeken van 2016. En door Pf – bij deze – door thema en aanpak tot het meest uitzonderlijke boek.

Eerst fotografeerde Marleen Sleeuwits steriele, onpersoonlijke ruimtes, dagelijks betreden en gezien door duizenden mensen zonder dat ze zich dat bewust zijn. Nu bouwt ze lege ruimtes om tot driedimensionale kunstwerken, versierd met overgebleven resten bouwmateriaal uit eerstgenoemde kantoor- vliegveld- en doorgangsruimtes. De foto’s die ze daarvan maakt zijn de eigenlijke kunstwerken. De ruimtes en voorwerpen zelf vernietigt ze weer; dat waren slechts grondstoffen. De Volkskrant: ‘Wat is ‘echt’, wat niet – het maakt niet uit. Hier wil je wel even blijven.’

Je geeft me een kunstwerk om naar te kijken, maar je pikt meteen de derde dimensie erin van me af.

“Misschien heb ik wel een vierde toegevoegd.”

Daar kan ik me wel in vinden. Een foto is natuurlijk per definitie altijd tweedimensionaal, maar de bedoeling is meestal dat je iets driedimensionaals ziet: het bruidspaar met opwaaiende trouwjurk, daarachter de koets en het vijvertje. Bij jou vloeit dat ineen: de driedimensionaliteit wordt opgeslokt, geabsorbeerd door jouw aanpak, maar verdwijnt niet. Misschien is dat jouw vierde dimensie.

“Ik zie mijn foto’s, groot, klein, zelf als fysieke objecten, ofschoon ze plat aan de muur hangen. In die zin heb ik inderdaad die derde dimensie toegevoegd aan mijn foto. Zo ben jij, toeschouwer, onderdeel van mijn werk geworden. Want jij moet je helemaal verhouden tot dat beeld. Anders gebeurt er niet wat jij zojuist als toeschouwer beschreef. Dat was meteen het probleem met mijn boek. Het fysieke, het object, is voor mij heel belangrijk. De afmeting, hoe het is geprint. Ik was bang dat ik dat element kwijt zou raken als ik de foto’s alleen maar in een boek zou plaatsen. Om dit te ondervangen heb ik voor het boek een maquette gebouwd, schaal een op zes, en daarin op schaal mijn foto’s gehangen. Dan zie je op foto de foto’s terug in de driedimensionaliteit van de maquette. Die maakt dat je ervaart door de expositie heen te lopen, zelf vóór de werken staat. Zo word je onderdeel. Maar, let wel, niet de maquette maar de foto is het eindresultaat.”

In die zin heb je die vierde dimensie toegevoegd met wat je te zeggen hebt? De samengang van twee- en driedimensionaliteit waarvan ik onderdeel ben geworden is mijn nieuwe werkelijkheid, waar ik vanaf dat moment rekening mee moet houden.

“Ja. Het zweeft er in elk geval tussenin. Twee-en-een-halfdimensionaal.”

Niet zo bescheiden! Maar terug naar de werkelijke werkelijkheid: de foto als tweedimensionale afdruk van het driedimensionale bruidspaar in het park. Wat is het verschil?

“Bij de trouwfoto is de maat der dingen geheel duidelijk. Bij mij is dat helemaal weg. Ik heb alleen al nooit mensen in mijn foto. Ook geen deuren of andere aanwijzingen van grootte. Daar speel ik erg mee: je moet op onderzoek gaan: waar kijk ik naar, wat is er mee, hoe steekt de ruimte in elkaar.

Dat doe ik omdat ik zelf puzzel met dit soort plekken. Zulke ruimtes intrigeren me. Al heel lang. Het begon op vliegvelden. Dat je eigenlijk niet weet: waar ben ik nou, wat voor tijd is het, dag of nacht, het kan altijd en overal ter wereld zijn. Die plekken zijn zo anoniem, zo inwisselbaar. Ik begon die te fotograferen, als een soort antifoto: er is geen beslissend moment. Hoe verhoudt je je als mens tot zulke plekken, kun je er een relatie mee aangaan.

In mijn nieuwere werk: de ruimtes die ik eerst zelf bouw, is dat heel letterlijk: kan ik met die ruimtes een relatie aangaan door ze in elkaar te timmeren, te doorboren, plakjes eraf te zagen, om te keren, weer uit elkaar te halen.”

Waar ben je dan naar op zoek?

“Misschien is het een speels, visueel onderzoek. Hoe je op die ruimtes grip kan krijgen. Waar bestaan ze uit. En dan is het ook een vertaling van mijn gevoel bij dit soort plekken.”

Ging je die zelf maken omdat de voorhanden plekken je niet meer genoeg waren?

“Na een paar jaar was ik daar wel klaar mee. Ik had wel gezegd wat ik wou zeggen. Ik had het idee dat ik door zelf ingrepen te doen m’n eigen stempel erop kon drukken.”

Je bent afgestudeerd fotograaf, maar van daaruit ook beeldend kunstenaar geworden.

“Steeds meer eigenlijk. Ik wou het verhaal verder brengen. Niet zozeer door er zelf elementen aan toe te voegen: een foto alleen kan ook kunst zijn. Daarin zie ik het verschil niet. Het ging me erom de ervaring dat ik me niet kon verhouden tot zo’n plek nog extremer te maken, nog persoonlijker. Een ruimte die zichzelf spiegelt, waardoor je niet weet waar boven of onder is, waar de plek eindigt en begint.”

Je werkt hier met een aantal andere bedrijfjes als een soort kraakwacht in een enorm leegstaand kantoorgebouw. Ik had verwacht hier die driedimensionale ruimtes en voorwerpen aan te treffen.

“Hier en elders in het pand heb ik wel wat gemaakt. Ik probeer steeds weer een laag toe te voegen aan de dimensies. Dat doe ik ook door alles te verkleinen tot die schaal een op zes en dan daar weer mee te spelen. Zo is het boek niet alleen een overzicht, maar ook, door weer een nieuwe dimensie, een nieuwe laag toe te voegen, zelf een nieuw kunstwerk.”

En zit dat dan meer in de beeldende-kunstkant of in de fotografiekant?

“Weet ik niet, ben ik niet zo mee bezig. Niet zo interessant. Ik maak wat ik maak, eet van twee walletjes: het mag bij beide aansluiting vinden. Die zie ik bij beeldende kunst, maar mijn werk, mijn achtergrond is toch fotografie. Beetje ertussenin.”

Nog eens: wat zoek je?

“Je begint een ruimte te bouwen, tot er een beeld ontstaat waarvan niet meer duidelijk is wat voor plek het is. Je weet niet wàt voor ruimte het is; Of je het kan aanraken, of het binnenste hol of bol is; hoe sta jij voor die ruimte. Kan je er als mens in. Die vervreemding moet erin zitten. Als vertaling van het gevoel dat ik op veel plekken heb, in allerlei steden. Het superanonieme, tijdelijke van zoveel van die plekken. Verbouwingen met systeemplafonds en tussenwandjes. Zonder karakter.”

Dat anonieme blijft bij jou. Of niet?

“Néé! Ik wil er juist grip op krijgen, het een smoel geven. Er juist verbinding mee maken. Of dat wel of niet lukt: altijd gaat het over díé strijd, die zoektocht.”

Lelijk gevraagd: wat heb ik daar als beschouwer mee te maken? Aardiger gevraagd: wat wil je met dit verhaal op mij overbrengen? Waarom maak je mij daar deelgenoot van?

“Ik ben niet de enige die dat ervaart.”

Zo begreep ik dat zojuist toen jij het vertelde: erkenning van die plekken.

“Over mijn oude werk heb ik gezegd: het is of die plekken achter je bewustzijn liggen. Je bent er wel maar je kan er niks mee.”

Neem dit lege kantoorgebouw van zestien verdiepingen: ‘wij’ hebben ons er jarenlang in moeten bewegen. Toen al als een alien, nu werk je er met tien bedrijfjes. “Inderdaad voor mij geschapen. Ik kan werken op een plek waar mijn werk over gaat. Dit is al de vierde plek. Heel groot, ik dwaal rond.”

Deze serie is gestart vanuit de financiële crisis van 2009. Daar moet jij ook nog weet van hebben.

“Zeker. Die bracht veel leegstand met zich mee. Dat was voor mij dè kans. Ik begon hier in 2010. Los van de maquette en de kleinere werken gebruik ik hele ruimtes.”

Oh. Dat zag ik niet op de foto’s. Wat ik hier zie kan net zo goed een van bovenaf gefotografeerd schoenendoosje zijn.

“Ik wil alleen niet prijsgeven waar ik de ruimtes heb gefotografeerd. Je krijgt wel aanwijzingen hoor, als je goed kijkt. Een stopcontact bijvoorbeeld. Nietjes. De foto’s zijn doorgaans groot, hangen in mijn galeries, In Berlijn of Den Haag. Veel staat op de website.”

Waarom fotografeer je geen mensen?

“Dan wordt meteen de schaal duidelijk. Dat wil ik niet. De mens doe mee als de toeschouwer ervóór.”

Ook het kunstwerk dat jij hebt gemaakt voor de foto vernietig je achteraf weer.

“De ruimtes. Niet alles. Niet de objecten. Die ruimtes op zich vind ik verder niet zo interessant. Ze werken alleen als foto. De maquette en de getransformeerde ruimte zijn halfproducten. Of minder.”

Door jouw werk heb ik één kunstenaar teruggevonden die bij mij als leek sterk overkomt: Mark Rothko.

“Die heb ik nog niet eerder gehoord. Ik ken wel z’n kleurgebruik, vlakken, composities. Je zoekt plekken waar alles samenvalt. Ja, dat doe ik ook. En dan eigenlijk alleen maar met materialen in die ruimtes voor handen zijn. Isolatiemateriaal, tl-buizen, kabel, draad, gips, verf, licht. Rommel, eigenlijk. Vieze spullen.”

Blijft het thema de vervreemding die de omgeving de mens aanbiedt?

“Het houvast vinden daarin, de verwondering.”

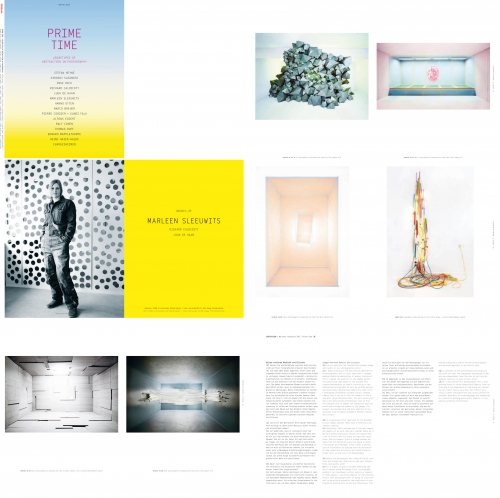

Prime Time: Archetypes of abstraction in Photography 2016

Interview by Ralf Hanselle

(German version below)

[Q] Can you describe the relationship between image and reality in your photographic works?

[A] I began pursuing a new and unusual approach in my photographic work in 2011. Back then I stopped making simple documentations of spaces. Instead of that I created the interiors in the images myself. The spaces that came about in the process were created deliberately so they’re convincing in two dimensionalÂ

photographs as well. My working method has essentially remained the same since then: First I photograph preliminary studies using a compact camera. Then I use an 8 x 10 inch camera for the final, more richly detailed shots. The early works still had a very pronounced architectonic look at first. The intention was to awaken the impression that you could walk through the spaces in the images. The images have become more and more abstract in the meantime. They’re places somewhere between reality and illusion.

[Q] Is it generally still important for the beholder of your images whether these have a reference to afamiliar reality?

[A] Absolutely. That’s perhaps one of the most important aspects in my work: What am I seeing? Where am I? How do I behave physically towards the spaces that I see in front of me? All these are important questions. With my images I build a bridge between the space that I’m illustrating and the space in which I find myself as a beholder. I thus create a perfect lack of orientation, by playing with the perception of time, space and occurrence. All these things no longer exist as one unit in my photographs.

[Q] Before you photograph, you create artificial interiors and sculptures. Where do you get your inspirations during this work?

[A] For a number of years I’ve been deforming spaces in vacant office buildings. First I investigate whether I can reconfigure certain objects or aspects of these spaces. I use found objects for the interiors which I then photograph later. In doing so I allow myself to be entirely guided by the conditions on site. Instead of working with existing architectures, this method allows me to take a far more psychological and personal approach in an artistic work.

[Q] In contrast to the installations and interiors you start off with, the subsequent photograph is flat and two-dimensional. Does the loss of the third dimension limit you in your artistic work?

[A] No. I was trained as a photographer first. I only devoted myself to three-dimensional objects later on. Thinking in two dimensions is therefore very normal for me. I don’t feel it as a loss. But I find it exciting to create situations this way, which confuse the beholder. Beholders of my photographs find themselves in a realistic-looking space which, however, is completely artificial nevertheless.

Bilder zwischen Realität und Illusion

[Q] Können Sie die Beziehung zwischen Bild und Realität auf Ihren fotografischen Arbeiten beschreiben?

[A] Ich habe 2011 damit begonnen, einen neuen und ungewöhnlichen Ansatz in meiner fotografischen Arbeit zu verfolgen. Damals habe ich aufgehört, einfache Dokumentationen von Räumen zu erschaffen. Stattdessen habe ich die Interieurs auf den Bildern selber kreiert. Die dabei entstandenen Räume sind extra dafürÂ

geschaffen worden, auch in zweidimensionalen Fotografien zu überzeugen. Meine Arbeitsweise ist seither im Wesentlichen gleich geblieben: Zunächst fotografiere ich Vorstudien mit einer kleinen Kamera. Dann nutze ich eine 8 x 10 inch Kamera für die finalen und detailreicheren Aufnahmen. Die frühen Arbeiten hatten zunächst noch eine sehr starke architektonische Anmutung. Es sollte der Eindruck erweckt werden, dass man durch die Räume auf den Bildern hindurchgehen könne. Mittlerweile sind die Bilder immer abstrakter geworden. Es sind Orte irgendwo zwischen Realität und Illusion.

[Q] Ist es für den Betrachter Ihrer Bilder überhaupt noch wichtig, ob diese einen Bezug zu einer vertrauten Wirklichkeit haben?

[A] Auf jeden Fall. Das ist vielleicht einer der wichtigsten Aspekte in meiner Arbeit: Was sehe ich? Wo bin ich? Wie verhalte ich mich körperlich zu den Räumen, die ich vor mir sehe? All das sind wichtige Fragen. Ich baue mit meinen Bildern eine Brücke zwischen dem Raum, den ich abbilde und dem Raum, in dem ich mich als Betrachter befinde. Ich erschaffe somit eine vollkommene Orientierungslosigkeit, indem ich mit der Wahrnehmung von Zeit, Raum und Ereignis spiele. All diese Dinge existieren auf meinen Fotografien nicht mehr als eine Einheit.

[Q] Bevor Sie fotografieren, erschaffen Sie künstliche Interieurs und Skulpturen. Woher nehmen Sie bei dieser Arbeit Ihre Inspirationen?

[A] Seit einigen Jahren deformiere ich Räume in leerstehenden Bürogebäuden. Ich untersuche zunächst, ob ich bestimmte Gegenstände oder Aspekte dieser Räume umgestalten kann. Ich nutze das Vorgefundene für die Interieurs, die ich dann später fotografiere. Dabeilasse ich mich ganz von den Bedingungen vor Ort leiten. Statt mit bereits existierenden Architekturen zu arbeiten, erlaubt mir diese Methode einen weit psychologischeren und persönlicheren Ansatz in einer künstlerischen Arbeit.

[Q] Im Gegensatz zu den Installationen und Interieurs mit denen Sie beginnen, ist die spätere Fotografie flach und zweidimensional. Beschränkt sie der Verlust der dritten Dimension in Ihrer künstlerischen Arbeit?

[A] Nein. Ich bin zunächst als Fotografin ausgebildet worden. Erst später habe ich mich den dreidimensionalen Objekten zugewandt. Das Denken in zwei Dimensionen ist für mich also sehr normal. Ich empfinde das nicht als Verlust. Aber ich finde es spannend, auf diese Weise Situationen zu erschaffen, die den Betrachter verwirren. Der Betrachter meiner Fotografien befindet sich in einem realistisch anmutendem Raum, der aber dennoch vollkommen künstlich ist.

Foam Fotografie Museum Amsterdam 2015

... Jacques Tati

For the past year I've been working on my first book publication, and in order to translate my work to the page I have created a model on a scale of 1:6. In this model I have presented my photographic works and objects (also to scale), and photographed them. These photos form the basis of the book. A task that can be disheartening at times, because if I make a cut that is half a millimetre off in the model, this will show in the photo as a half-metre, gaping hole. During this process I often thought of the movie Playtime by Jacques Tati. For this film in 1967, he recreated an entire city to scale, named Tativille. The film is about Monsieur Hulot who gets lost in this hypermodern city, but to me it is the skyscrapers, the concrete, steel, glass, and reflections that play the leading role. The result is, even today, incredibly modern and inspiring. What also intrigues me, are the photos from the making-of, where you can see how decor and reality blend together seamlessly. Cars cut out of cardboard are combined with real vehicles and entire buildings are built in perspective. For my own photographic works, I transform spaces inside vacant office buildings and try to enhance or alienate the characteristics that can be found within the space. The images that originate from this process lie between reality and illusion. With a little imagination, they could be Tativille interiors.

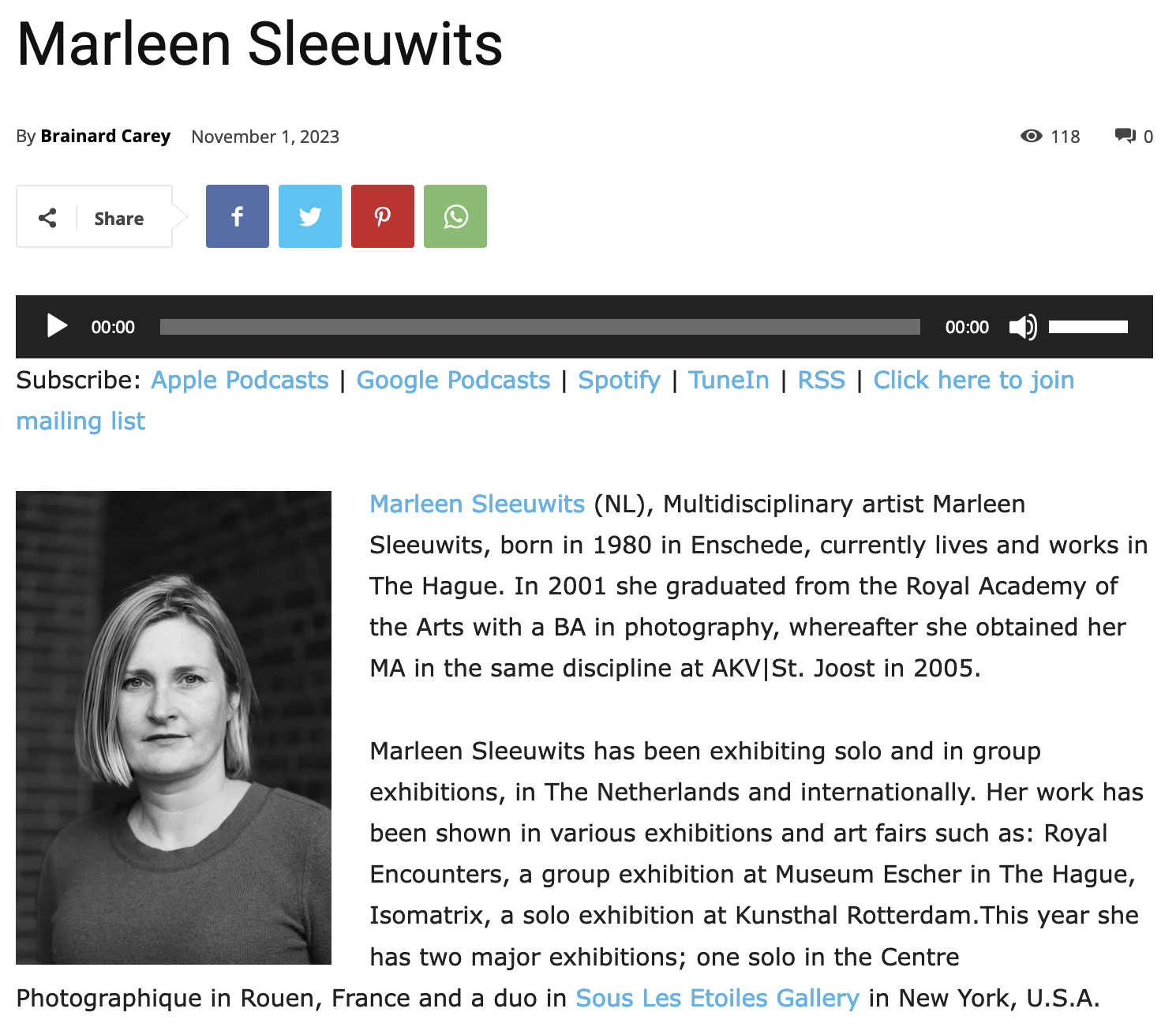

About Marleen Sleeuwits

Marleen Sleeuwits (1980) obtained her BA diploma from the Koninklijke Academie van Beeldende Kunsten in 2003, and her MA from the Avans Hogeschool in 2005. Marleen Sleeuwits was chosen as one of the sixteen Talents of Foam Magazine #32 / Talent issue. Her first publication will be launched in the fall.

Urbanautica 2015

by Nicolette Klerk

Tell us about your approach to photography, how it started. What are your memories of your first shots?

Marleen Sleeuwits (MS): When I was fourteen I started a photography-course at a local community centre. I mostly took portraits of friends in a home-built studio in the attic, using all my parents lampshades. I was very lucky this class was taught by a very passionate photographer. He made me explore all kind of techniques and genres and I could always use his equipment and dark room. Thinking back at it he was probably the best teacher I ever had. So after highschool it was not hard for me to decide what do next: art school. Luckily I got accepted at the Royal Academy of Arts in The Hague being just seventeen.

How did your research evolve with respect to those early days?

MS: Art Academy was a lot about learning techniques and writing down concepts. The downside for me was that I didn’t really learn to explore my own style and interests. This was something I missed once I got graduated and it was the reason I applied for a master in Breda. Since then my work has followed quite a focused trajectory; from photographing architectural spaces, to constructing them myself, to eloping from the photographic frame altogether into physical space itself. It’s actually quite recently I have found my own approach and I learned to trust my intuition more. This was very liberating because my process is now much more organic: Making and thinking simultaneously, so I guess that’s much more like it was when I was fourteen.

When photography is a (sub)division: how is photography related within your work?

MS: Although photography is still very important in my work the actual ‘taking-photo-part’ is becoming less and less. Mostly I work for weeks or even months on a space: constructing, painting, drilling etc. I always take shots with a digital camera to see how things work out 2-dimensionally and once I’m satisfied I take just one shot with my 8 x 10 inch camera.

What do you think is important for the emergence of your work? What makes a picture a strong image?

MS: To me it’s important that one photo tells a specific part of the overall concept I’m trying to get across. In one work it can be more about materials and in another it can be more about scale and how you relate to space as an individual.

About your work now. Can you describe your personal research in general?

MS: I let the elements in the interior/ office building guide me and that is the starting point of my work. I work with materials I encounter there. Also I have a lot of ideas which I make sketches of or that I write down. Most of the time I start with one of these vague plans. While I’m constructing the space I always take pictures with a small digital camera to see if things work the way I want. This is seldom the case so then I keep changing the space until all pieces come together. This process is quite intuitive.

What are your considerations?

MS: In my photography and objects I research interiors in which you don’t feel connected to a speciï¬c place or time. It is a conflicted feeling that certain places can evoke inside of me.

What is your main source of inspiration?

MS: For me inspiration can come from many things. From just wandering through empty buildings to visiting a hardware store to endless surfing online.

Is there any contemporary artist or photographer, even if young and emerging, who influenced you in a way?

MS: I don’t know if I’m influenced but I have for a long time loved the work of Lynne Cohen. She also took photos of interiors which are really surreal. Nowadays I enjoy artists like Andre Kruysen, Michiel Kluiters, Katja Mater or Anouk Kruithof because they search for the boundaries of photography. They combine photography, sculpture with installation and drawing.

Tell us about your latest project ‘Interiors’

MS: Recently I have been deforming spaces in vacant ofï¬ce buildings. I investigate whether I can reconstruct certain qualities of the interiors I photographed previously. I let the aspects in the interior guide me when working with materials I encounter there. These are usually non-durable materials like sticking tiles, false ceilings or insulation material.These materials give the interiors the capability to change their identity rapidly.

Rather than photographing existing architecture, this way of working enables more psychological spaces to appear that convey the feeling of disconnection in a more personal and profound manner. The images create a place with something in between reality and illusion. As if there is a gap between seeing what is there and what is not. In my spatial works and installations this experience becomes even more tangible.

Which projects are you working on now and are there plans or ‘needs’ for the future?

MS: For a few years I’ve been thinking about making a photobook but I always saw too many obstacles. In my photoworks scale and the actual sizes are crucial to the experience of it. I had no idea how I could get these aspects across in bookform. If I just put the pictures in a book this important aspect of my work would completely be lost. Last summer I came up with the idea to build an enormous maquette, scale 1:6. This maquette represents a fictive exhibition-space where all my work is displayed. Flipping through the book will seem like you walk through a real exhibition. I love the idea that the maquette solves the problem of scale and even brings an a extra layer to my work.The book will be launched at the end of this year by Onomatopee Publishers. Besides this huge project I’m working on my first solo show in my new gallery FeldbuschWiesner in Berlin. This exhibition will open this coming december.

Is there any show or film you’ve seen recently that you find inspiring?

MS: I just saw the solo exhibition of Geert Goiris in Foam and loved it!

One to three books of photography or art that you recommend?

1. ‘Multiple densities’ by Katja Mater;

2. ‘La Hütte Royal’, 2013 by Thorsten Brinkman

3. ‘New scenes’ by Esther Tielemans

How do you see the future of photography in general evolve?

MS: I guess this world becomes more visual so I think the language of photography becomes more and more diverse and therefore more interesting.

What do you think about photography in the era of digital and social networking?

MS: Personally I use Facebook to give people insight in my process, inspiration and thoughts behind my works. I think it’s a great way to make my work more accessible. And of course I use it to tell about upcoming exhibitions.

How do you combine your work and private life?

MS: At the moment this is quite hard actually. I have a son who is one and a half years old and and I am expecting another baby in a few months. In the meantime work didn’t get any slower, so this means there just isn’t enough time for all the ideas and plans I have. I find it annoying that practical things always seem to go on and that new things at the studio come last. Also visiting exhibitions from others is something I don’t do as often as I used to but one day, one day I will have time…

Do your prefer to work alone or as a team?

MS: Most of the time I work on my own and I must admit I love it that way. Over the last few years I occasionally have had an intern to assist me; helping out with practical matters like building installations. That’s always fun and very efficient especially in times, like now, when a lot needs to be done. At the moment I am working on my first publication and on a big solo show. Despite the fact that working together is more efficient I feel I come to better ideas when I work alone. So this is a dilemma.

So is it hard to manage all the deadlines?

MS: Actually I’m quite good in planning my work and meeting deadlines. This is because my character is quite chaotic and stressed. If I don’t organize everything very well my head is overflowing quite fast. So you won’t find me installing my work the night before an opening. The last couple of years in addition to my daily to do list I also make a schedule for one year, most of the exhibitions and big projects like the book launch are scheduled way ahead anyway, and this helps me to keep an overview.

What about locations for your works?

MS: Over the years I have made many connections with anti-squad organizations and many office buildings in The Hague are empty. If I have to leave a certain place most of the time something fitting comes along quite soon. I also try not to make to many demands and let the restrictions I find guide me to make new works.

Website Wandering Bears 2011

Â

1. Would you consider your work in any way sculptural, or do you define it purely as installation?

The spaces I create are made just to work in a flat photo. I often change one specific corner of a room and most of the time this is only interesting when seen from one specific angle. However I feel some of these constructed spaces are interesting as an installation. This is something I am starting to explore more within my new work. My framed photo works have always been very sculptural because of their physic qualities. Their size, sharpness and colours are very important. However this causes a problem as the prints have the best effect when you see them for real, standing in front of them, but less so in a book or on the internet.

Â

2. You mentioned that you are currently working with 3D objects, what is the inspiration behind this new direction?

Actually not really 3 dimensional objects but I would like to show some of the physical interventions I make for my photographs in an exhibition itself. I feel these ‘sculptures’ will work as an installation combined with my photoworks. It’s something I am just starting to explore so there are no concrete results yet.

3. For me, your work thrives in print, hung in large spaces. What is your relation to the gallery, do you see it as the final output for your work?

It’s true that my photo’s work well in a gallery. They need a certain level of concentration. I like it that the person who looks at my work feels he can almost enter the space that is displayed. All the details in the print are incredibly sharp because I work with an 8 x 10 camera. It’s like you can really touch these things. Most of the time it results in that people walk back and forth towards the work. A gallery or museum is of course perfect for that, no distractions. Early this year my work was exhibited in an art fair in Rotterdam. This fair was situated in a office building from the seventies. It had exactly the same atmosphere as my photographs. This location worked really well combined with my exhibition, like having a double vision.

Â

4. When you enter a space, do you have a clearly planned outcome for your image, or do you work mostly relying on instinct?

Not really. I let the aspects within the interior guide me and that is the starting point of my work. I work with materials I encounter in the spaces I portray. Also I have a lot of ideas which I make from sketches or that I write down. Most of the time I start with one of these vague plans. While I’m constructing the space I always take pictures with a small digital camera to see if things work the way I want. However this is seldom the case, so then I keep changing the space until all pieces come together. This process is quite intuitive.

Â

5. I admire that your work presents an ‘ethos’ and direction rather than a variety of varied projects, dedicating yourself to developing this process of construction and deconstruction. Do you see yourself working in this way in the future?

Yes I’m definitely not finished with this Interior project. Thankfully my areas of attention change so it stays interesting for me as well. For instance my work has undergone a big change over the past years, from working in a photographic way to deforming and constructing my own spaces. This was a big turnaround in my way of working and thinking. But it’s true that what I am trying to communicate has not changed essentially, only the way I say it.

Â

6. I understand you produce your images in an office building, are you able to describe this process?

I now work in my third empty office building. In Holland there are a lot of empty office buildings in this moment due to the current financial crisis. Two years ago I started renting only one space in an office buildings. This ment I had to change the same space over and over again. (Interior no. 24 to 29) It was a very interesting process because the work became more focussed on how you perceive this space. Recently I moved into an empty office building which is 16 stories high. It feels like I have 100 blank canvasses.

7. How do you approach commissions? Do you ever feel constricted within the environments you work, given that your personal work displays a large degree of intervention and construction on your behalf?

The commissions I work on are quite diverse. Sometimes I work for architects and I can follow a building through the complete process of constructing. Also I work for product designers. Working in a commission is of course more strict then my own practice. Most of my commissioned work comes from clients who know my art work and want something with the same atmosphere. Sometimes I can use these jobs to try something out for my own work. I havent produced a lot of commissions where I constructed spaces, so hopefully the opportunity will come in the future.

Â

8. Do you have a favourite interior / image you created?

If everything goes well, it’s the piece I just finished.

Â

9. Can you remember the moment your practice clicked, when you understood this was the approach to photography you wanted to pursue?

It was actually quite recently that I felt that I had finally found my own language. The art academy I attended was mainly focussed on concept. Only in the last years I learned to trust more on my intuition. This was very liberating because my process is now much more organic: Making and thinking simultaneously. I feel that this suits me much better.

Foam Magazine # 32 Talent Issue 2012

Born in 1980 in Enschede, the Netherlands, Marleen Sleeuwits did a BA at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague, followed by an MA in Photography at the Art Academy of Breda (2003-2005). She currently lives and works in The Hague and is represented by Liefhertje and de Grote Witte Reus. In her work, Marleen Sleeuwits investigates the state of disconnection that arises from the spaces she has sought out, such as dead corners of office buildings, waiting rooms or empty corridors in hotels. More recently, Sleeuwits has also started constructing new environments within such spaces, using materials she finds there, such as laminate flooring, tape, sticking tiles etc.

You did an M.A. in photography at the Art Academy in Breda, following on from your BA in art. What did the M.A. course add to your photographic practice?

My Bachelor education in The Hague was mainly focused on commercial photography. I learned a lot about photography technique and presentation. After graduation I worked two years as a commercial photographer but this didn't feel like it was something I wanted to do for the rest of my life. I started the MA in Breda to find out about my own fascinations and how to work on my own projects. The best thing about Breda was the discussion. Every week some students presented their latest work to a group of students, teachers and guest teachers. With so much expertise and opinions I learned how to communicate about my work and to trust my ideas and defend them.

What first attracted you to interiors and the feelings they elicit in you?

I started to take photos of interiors when I was doing a series about airports. I began work on this series after watching a documentary about a businessman, who travelled the world for his job. He spent most of his time in convention centres and around airports. One day he woke up in his hotel and had totally forgotten where he was. Looking out of the window didn't give him any clues. He had to check his diary to find out. I thought this experience was quite surreal. It related to a feeling I sometimes have in airports or suburban areas myself. I visualized this by starting to take photos at different airports and ended up with the underground areas, such as endless labyrinths of moving staircases, hallways and waiting rooms. They almost seem to be designed to purposely disorientate. You loose all sense of direction, and usually, there is no daylight so you have no idea what time of day it is.

Interiors are common subjects, or much photographed places. How did impose your way of seeing on those spaces?

Sometimes I search for months before I even get my camera out of my suitcase. The first important element for me is that it's not instantly clear how the space is put together, such as a hallway that seems to lead nowhere or a fake wall suddenly dividing the room. Also, structures and colours are important to me. The places I photograph are mostly typically sick buildings. But my pictures are not about how horrible these places are. They are about not being able to connect with the place you are in. I need you to feel attracted to the space as well, so you don't really know whether to hate or love it. I try to achieve that by choosing spaces with attractive bright colours, interesting structures and exciting light.

Is there any manipulation done at all in your First series (e.g. layering, Photoshop to add or remove pieces) or are they as you find them, with your specific framing?

I work with an analogue camera, an 8 x 10 inch technical camera. This is not for romantic reasons; it's (still) the best way to get the sharpest image possible. When the film is developed I scan it and use Photoshop to alter whatever I feel is necessary to make the image work. Sometimes changing complete ceilings and floors and sometimes just a small detail like a spot on the floor.

My work isn't a document about certain existing places so for me this is not an issue. Another reason for me to use Photoshop is to create a certain suspense whether the place in the photo is real. By choosing carefully which traces and details I want to keep, I end up with the perfect tension. These and other technical choices like print size, sharpness in the details and structures give my photography a physical quality. I want the viewer to step inside and be able to relate physically to the portrayed space.

For your second series, where you deform or alter spaces in vacant office buildings yourself, do you know immediately what the space needs? What is your working process in deciding what the installation will be?

For this new series I don't know exactly what I want to do with a certain space before I start. I don't make sketches but experiment with the space itself and with materials already present in the building such as insulation-material, ceiling system, TL light boxes, carpet, etc. Sometimes I add things that I buy at the hardware store. This is a big turnaround in my way of working. Building the spaces myself enables me to work in a more intuitive way and to be less dependent on what I actually encounter. I am able to research a lot in a relatively short period of time, by making compositions of various materials and photographing it with a small snapshot camera and seeing if it will work in a 2D composition. Rather than existing architecture, this way of working enables me to create more psychological spaces that translate this feeling of disconnection in a more personal way.

There seem to be a number of talented young photographers emerging from the Netherlands. What do you think it is about the country and its teaching system, that's ensuring this talent is born?

I agree with you that there are many young talented photographers from The Netherlands. A lot of them make great work and experiment with the medium, combining photography with video, sculpture and installations. They come from different Art Academies from The Hague, Breda, Amsterdam and Utrecht. It seems that talents inspire and encourage each other.

Another important element is that the cultural climate for emerging artist in The Netherlands used to be very good. There were several subsidies and grants that enabled young artist to develop their work. I think this is very important because it takes time to find your own way and grow as an artist. Unfortunately due to enormous cuts on culture in The Netherlands these financial arrangements are rapidly disappearing. I fear that in the near future this fertile cultural landscape will disappear and it will be very difficult for art academy graduates to flourish.

You have taught photography at Fotogram in Amsterdam and at Beeldfabriek Rotterdam. If you were to dilute your lectures into a single message, what is the message you were most trying to get across to your students?

Finding a balance between concept and intuition. Ideally they work on both simultaneously. Students can be very vulnerable so encouraging them to make lots of work, experiment and not to think in dogmas for me is the most important.

What are you currently working on?

I've been changing and constructing spaces for over a year now. I'm definitely not finished with that. This new method made me more aware of the fact that textures and surfaces play an increasingly important role in my work. At this moment I'm very interested in working with cheap, fake, non-durable materials, such as laminate flooring, slab tiles or ceiling systems.

For me it’s conceptually interesting because they immediately refer to the places in my previous work.

At the moment I'm also working on a plan to exhibit my work in a spatial presentation. The installations I build for my photos are sometimes very interesting in themselves. I want to experiment with presenting them in combination with the photo works.

Unseen Magazine 2015

What first attracted you to the non-descript, in-between spaces that feature in your work? Is it an interest based on attraction or a more negative response?

I would say it's a bit of both and this is what makes them so interesting for me. I don't know whether to hate or love them, nor how to connect with them. I started with the interior series after seeing a documentary about a businessman who travelled the whole world. One day he woke up not knowing where he was. Looking out of the window didn't give him any clues. I wanted to translate this surreal experience into a series so I started taking photographs at airports all over Europe. I thought it was fascinating that there seems to be no actual place or time there. The interiors I photographed later have the same feeling; they could be a shopping mall in Shanghai in the middle of the night or a hospital in the Netherlands during the day. Not being able to relate to them was very interesting to me. Like making a sort of anti-photograph.

For some of your projects you have relocated to the building you are working in. Are your interventions based on your own psychological response to the space?

My interventions, whether they are photo-works, installations or sculptures, are definitely a psychological response to me being present in these spaces. Like my earlier work, it's always about finding a way of connecting with these kind of generic spaces, both physical and psychological. With my new work, where I deform and deconstruct empty offices, this is literally the case. By literally, I mean really turning them inside out: drilling through them, peeling off the walls, taking out the ceiling-plates and screwing the plates back on the wall.

I wanted to investigate whether I could reconstruct certain qualities of the interiors I had photographed previously. Rather than photographing existing architecture, this way of working creates a more psychological space that conveys the feeling of disconnect in a more personal and profound manner. The images create a place in-between reality and illusion, as if there is a gap between seeing what is there and what is not. I let aspects of the interior guide me, and I work with materials I encounter there. These are usually non-durable materials like sticking tiles, false ceilings or insulation material. These materials give the interiors the capability to change their identity rapidly.

Your work has followed a focused trajectory – from photographing architectural spaces, to constructing them yourself, to eloping from the photographic frame altogether into physical space itself. Why this direction?

Through my work in these empty office towers, I have gained an insight into how this same characteristic of estrangement in my photography can also be found in a space, installation or sculpture itself. In the past two years I’ve been examining how I could present this in an exhibition space. My main motivation for combining these constructed spaces and installations with my photo-works is to break a certain barrier that a photography exhibition has. After all, it is as if you look into the room through a window. By combining these three elements, a more tangible and personal experience will arise.

The next step in this journey is the photobook, which you will be showing a dummy of at Unseen this year. Could you tell us about this project?

For a few years I've been thinking about making a photobook but I always saw too many problems. In my photo-works, scale is crucial to the viewer’s experience. Besides that, I work with an 8 x 10 inch camera with makes the details in my prints so sharp it seems like you can actually touch them. I had no idea how I could get these aspects across in book form. If I just put the pictures in a book, this would completely be lost. Last summer, together with graphic designer Karin Mientjes, I came up with the idea of building an enormous maquette. This maquette represents a fictional exhibition-space where all my works are displayed. Flipping through the book will be like walking through a real exhibition.